Richard Weaver bewords the South’s view of war as a

‘ritual’ or ‘game’ that must be performed because it is in man’s being to fight. However, rituals and games are always offered

to, or done for the sake of, another. To

whom do Dixie’s knights offer this ritual of

war? Largely, to the shame of the South,

to themselves: Southerners not possessed

by the demonic ‘West is best’ ideology generally have fought (whether personal

duels or wider wars) because of an affront to their honor; that is, their

high-minded view of themselves has been wounded and now they must do battle

with the offender to repair their reputation before others and to cheer their

own hurt feelings (‘Southern Chivalry and Total War’, pgs. 163-4).

It

scarcely need be said that this is not a Christian but rather a humanistic approach

to war. There are, though, redeeming

aspects in the Southern view of war.

Firstly,

war as a ritual or game is by its nature fought according to rules, which helps

keep the fighters from engaging in the most destructive and barbarous acts possible

during battle (‘Southern Chivalry and Total War’, p. 164).

Also,

a war to sooðe one’s hurt pride will most of the time be of a more limited kind

than one fought for the sake of a religiously tinged ideology (fighting to

‘spread democracy’, for ‘economic freedom’, ‘women’s rights’, and so on).

(This

may clearen to some extent why the persecutions of Christians under the Roman

emperors were less severe than those under the communists in Russia and Eastern

Europe or under the Islamic State’s fighters today in the Middle East and

Africa: The former centered on the

worship of a living man, the emperor, each of whose particular virtues and

vices would determine the harshness of the punishments he inflicted on the

Christians if he felt threatened or slighted by them, thus setting some bounds

to his acts. The latter are based on

inhuman ideas (godless materialism; the religious conquest of all peoples) that

neither know nor are able to impart mercy or any other boundaries.)

Furthermore,

there are utterances by those most representative of the Souð, like Robert E.

Lee, about ‘the limitations of soldiering as a profession’: It ‘does not prepare men for the pursuits of

civilian life’ (Weaver, ‘Lee the Philosopher’, p. 176).

And

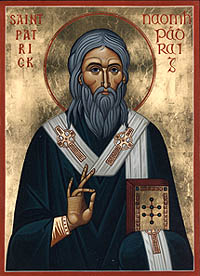

there is Prof Weaver’s own important insight - mirroring the actions of the South’s

patron saint, King Ælfred the Great, after he had defeated the Danes in England

- ‘It [the materialistic, spoiled, short-sighted middle class--W.G.] cannot see

that after one has defeated the enemy, one has the responsibility of saving his

soul’ (‘Southern Chivalry’, p. 169).

This mind-set is one that sets the South apart from those who shallowly

seek the ‘complete destruction of the enemy, so . . . we won’t be at the

expense of having to do this [i.e., fight them--W. G.] again’ (p. 169).

Prof

Weaver pondered how mankind’s warlike bent might be safely bounded so that

peace might come to the world (‘Lee’, p. 174).

The answer he sought came with the coming of Christianity; and more

specifically, with the coming of organized Christian monasticism. Robert Boenig in his ‘Introduction’ to Anglo-Saxon Spirituality quoted André

Vauchez on the monasticism of Dixie’s Old

English forefathers:

By presenting religious life primarily as a

ceaseless struggle against the “Ancient Foe,” monastic spirituality awakened

widespread reverberation within a warlike society whose secular ethic . . .

favored related values (p. 42).

For

Orthodox Christians in general (who are all called to a life of asceticism,

just like monks), but especially for the monks who leave the cares of the world

to focus their attention only on the salvation of their souls (i.e., union with

God), life is a war with the inner passions and the demons and the devil, who

seek our downfall. Here, then, is where

the Southerner’s yearning for a fight, and all mankind’s, may be safely

directed, just as it was with the South’s violent Anglo-Saxon and Celtic

forebears: to battle together with our

brothers (or sisters) in the monasteries with the unseen forces in the ghostly

realms for the salvation of our souls and bodies. And may those of us still living in the world

follow well their ensample, as Christians throughout the ages have sought to do.

Works Cited

Robert Boenig, ‘Introduction’, Anglo-Saxon Spirituality: Selected Writings, Boenig trans., Mahwah,

Nj., Paulist Press, 2000.

Richard Weaver, ‘Southern Chivalry and Total War’

[1945], The Southern Essays of Richard M.

Weaver, Curtis, III and Thompson, Jr., eds., Indianapolis, Ind.,

LibertyPress, 1987.

--, ‘Lee the Philosopher’ [1948], The Southern Essays of Richard M. Weaver,

Curtis, III and Thompson, Jr., eds., Indianapolis,

Ind., LibertyPress, 1987.