The

South is a place where a lot of focus has been placed on the Lord Jesus

Christ. Since the Great Revival in the

South that started in Cane Ridge, Kentucky, in 1801, this focus has tended to

be framed by the idea of a ‘personal relationship’ with Jesus Christ. But there is a problem with this. Yes, the Lord Jesus did take on human flesh

and condescends to our weaknesses, but to restrict our relations with Christ to

fallen human limitations, turning Him into something like a cosmic best buddy,

is a tragic error.

We

see this limiting of our relations in the writings of various Protestant

Evangelicals. Joyce Meyer gives a good

ensample:

God wants to be involved

in everything we do. He wants us to fellowship with Him, which means

communicating with Him throughout our day just like we do with someone who's

our close friend or family member.

Knowing God loves us, loving Him, spending time with Him, and being grateful

for what He's done and is doing in our lives can help us have a real

relationship with Him.

But

we were not made for external relationships with God, mankind, or the

creation. We were made for union with

all of them. The hardened boundaries

between ourselves and the things around us and God are a result of the fall. It will not be like this in the age to

come. We get a foretaste of it now in the

sacramental life of the Orthodox Church, and also in true prayer when men and

women unite all things in the heart, the spiritual center of human beings

(which prayer, it must be said, cannot be separated from the ascetical,

liturgical, sacramental life of the Church).

On

union with Christ our Lord, which is the fullest potential of our ‘personal

relationship’ with Him, here are some words from the Orthodox pastor,

Archbishop Chrysostomos:

. . .

Keeping in mind these

general principles with regard to the source of genuine theology (empirical theology),

let us examine what St. Gregory Palamas says about the person. To begin with,

we must say something about the Orthodox understanding of man. Man exists both

in essence and in hypostasis (and the word hypostasis is one

which Palamas seems to prefer over the word person, having drawn much of his

language in this regard from both St. Basil the Great and St. John of

Damascus). The essence of man (bear in mind that this word derives

ultimately from the verb to be, as Metropolitan Ierotheos reminds us) describes

his state of being, which he shares with all others. His hypostasis (person),

however, is that which distinguishes him from others. (Needless to say, one

should not naïvely confuse the terms used here in describing the human being

with the Hypostasis and Essence of God, which have wholly different

meanings and which apply to God alone. The Essence of God is ineffable; and the

Hypostasis of God is uncreated, while that of man is created.)

The human person is

the hypostatic manifestation of the human essence, the realization of who

a human being is as an individual: being, again, common in his essence but

individual in his hypostasis or person, as St. Gregory Palamas affirms.

It is primarily the human person to which the therapeutic and salvific methods

of Hesychasm, as the spiritual teachings of Palamas are called, are directed.

The cleaning and enlightenment of the individual human mind, the purification

of the human heart, and the restoration of the passions (which have been

misdirected and perverted, as a result of the Fall) constitute the Hesychastic

way of life. And the way of life that effects these things leads to the

restoration of the individual, the human person, who freely turns from a

life of sin to one of synergy with God. In short, one can say, though risking

theological difficulties in overstating this point, that the restoration of the

human being in Christ centers on the person, on the restoration of the

person, and on the cure of the process of disease which separates the

individual from the full realization of his potential in Christ.

In the purest

anthropology of the Fathers, expressed perfectly in the Hesychastic teachings

of St. Gregory Palamas, we come to understand that the essence of man, his

being, has been restored through the divinization of human nature by the

Incarnation of Christ, Who, in His Resurrection, lifted human existence above

what it was even before the Fall. The personal salvation of the human being

lies in his free acceptance of the potential for restoration in Christ, his

ascetic struggle to free himself from the taint and illness of sin, and his

restoration of the human person, his hypostasis, through the vision of

God. And this vision of God, according to St. Gregory Palamas, is communion

with God, the divinization of the human person (theosis), and his union

in energy with Christ. In this divinization by Grace, man comes to an intimate

knowledge of God. His mind cleansed and enlightened, his heart purified, and

his passions cleansed and directed towards the love and attainment of holiness,

man finds salvation.

And once more, this

salvation is personal, centered on the distinct human being who draws on

his essence—renewed in Christ—and who, in his person, becomes a small Jesus

Christ within Jesus Christ, to quote one Church Father. So it is that Jesus

Christ is our personal Lord and our Savior. In this profound sense of the

personal, and in an apocalyptic encounter with redemption (for salvation is

closely united to spiritual vision and to the noetic revelation and knowledge

of God), we find, through experience, what the more fundamentalistic

Protestant Evangelicals understand only in empty form. We know through the

attainment of true personhood in Christ, which is the enlightenment or

salvation of man, what these seekers know only intellectually and in terms of a

theology of affirmation and commitment crippled by the unrestored senses and

passions.

It behooves me to

note, here, that God transcends all human categories of thought, all human

conceptualization, and even our understanding of His existence. The personal

experience of the redemption of Christ, therefore, occurs beyond the dimensions

of the human intellect, as I said above, since the true encounter with Christ

is an encounter with God Himself. This encounter is the result of our union

with God's Energies, and thus occurs noetically and spiritually, through the

mind made new in Christ, the heart transformed by Grace, and the person

restored to the image of God in union, by Grace, with the God-Man. Divine

vision is, in effect, vision beyond vision, just as personhood in Christ is

beyond the personal as we understand it, since the fallen personality is not a

true person, but the product of passions and fallen proclivities.

In conclusion, I

should emphasize that the therapeutic path towards the restoration of

personhood in Christ is, and must be, focused, of course, on the life of

the Mysteries, which are the very life of the Church and which cannot be

separated from the Church in any manner whatsoever: among other things, the

emptying-out (kenosis) of sin through confession and the infusion into our

hearts, joints, and reins of the Body and Blood of Christ in the Holy

Eucharist. The spiritual faculty of man, the noetic faculty, having been

displaced from its natural place in the heart, as St. Gregory Palamas teaches

us, must be brought back into the heart, back to its natural place, so that the

human person can be restored and, cleansed by the Mysteries, rise above his own

nature, attaining what is above nature, transcending human nature through union

with Christ. As a result of this, the human being transcends even his own

person, his restoration in Christ touching on all mankind. Gaining the gifts of

the Spirit, he sees all things clearly, not only for himself, as St. Gregory

writes, but revealing what he sees to others, and thus helping them to gain

their salvation through the vision of God.6 In this sense, Christ is not only

our personal Lord and Savior, but He is also the Universal Person, Who renews

us each individually and, so made manifest in us, reveals to us a far greater

dimension of personal salvation than we can imagine.

One

other note on the Evangelical view of the personal relationship with God: It is opposed to the apostolic command to

practice asceticism, to the idea that we must war against our corrupted

passions, in order to prepare ourselves for union with Christ and to be able to

live a holy life. Quoting again from the

same Joyce Meyer article as above:

When we have a real

relationship with God through Christ, life gets exciting because He stirs up a

passion inside us to love people—and we don't have to struggle to do the things

He calls us to do. It just happens naturally.

The

importance of the differing approaches has been touched on by the Archbishop

above and will be seen again in the passage from St Symeon below.

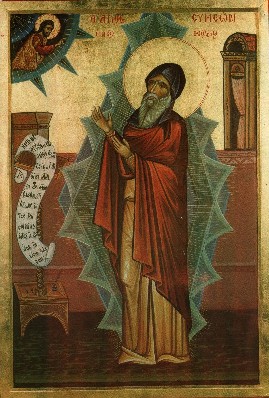

The

iconography of both Evangelicals and Orthodox illustrates well the points we

have been discussing.

On

the Evangelical side, this expresses their ideas of personal relationship very

well, the ‘Jesus as a good buddy/close friend’ teaching, where the divinity of

Christ is swallowed up by his humanity:

The

Orthodox Church, as we said above, also emphasizes the true humanity, the

approachableness of Christ:

But

she does not lose sight of the fact that He is, in addition to being perfect

man, also perfect God. Therefore, a fully

realized ‘relationship’ (if that word must be used) with Christ will take place

on a different plane of existence than the interpersonal relationships fallen

human beings are accustomed to. The Lord

Jesus is more than just a supernatural best friend Who hugs us and gives us

emotional support. He gives us life and

knowledge of Himself and etc. by our union with His resurrected, glorified, and

ascended Body through holy baptism:

The

journey toward full union with Christ is expressed beautifully by one of the

Orthodox Church’s great saints, Symeon the New Theologian (+1022). In his account, one will see something of the

poverty of the usual Evangelical Protestant approach to the Christian life:

A man by

the name of George, young in age - he was about twenty - was living in

Constantinople during our own times. He was good-looking, and so studied in

dress, manners and gait, that some of those who take note only of outer

appearances and harshly judge the behavior of others began to harbor malicious

suspicions about him. This young man, then, made the acquaintance of a holy

monk who lived in one of the monasteries in the city; and to him he opened his

soul and from him he received a short rule which he had to keep in mind. He

also asked him for a book giving an account of the ways of monks and their

ascetic practices; so the elder gave him the work of Mark the Monk, On

the Spiritual Law. This the young man accepted as though

it had been sent by God Himself, and in the expectation that he would reap

richly from it he read it from end to end with eagerness and attention. And though

he benefited from the whole work, there were three passages only which he fixed

in his heart.

The first

of these three passages read as follows: 'If you desire spiritual health,

listen to your conscience, do all it tells you, and you will benefit.' The

second passage read: 'He who seeks the energies of the Holy Spirit before he

has actively observed the commandments is like someone who sells himself into

slavery and who, as soon as he is bought, asks to be given his freedom while

still keeping his purchase-money.' And the third passage said the following:

'Blind is the man crying out and saying: "Son of David, have mercy upon

me" (Luke 18:38). He prays with his body alone, and not yet with spiritual

knowledge. But when the man once blind received his sight and saw the Lord, he

acknowledged Him no longer as the Son of David but as the Son of God, and

worshipped Him' (cf. John 9:38).

On reading

these three passages the young man was struck with awe and fully believed that

if he examined his conscience he would benefit, that if he practiced the

commandments he would experience the energy of the Holy Spirit, and that

through the grace of the Holy Spirit he would recover his spiritual vision and

would see the Lord. Wounded thus with love and desire for the Lord, he

expectantly sought His primal beauty, however hidden it might be. And, he

assured me, he did nothing else except carry out every evening, before he went

to bed, the short rule given to him by the holy elder. When his conscience told

him, 'Make more prostrations, recite additional psalms, and repeat "Lord,

have mercy" more often, for you can do so', he readily and unhesitatingly

obeyed, and did everything as though asked to do it by God Himself. And from

that time on he never went to bed with his conscience reproaching him and

saying, 'Why have you not done this?’ Thus, as he followed it scrupulously, and

as daily it increased its demands, in a few days he had greatly added to his

evening office.

During the

day he was in charge of a patrician's household and each day he went to the

palace, engaging in the tasks demanded by such a life, so that no one was aware

of his other pursuits. Every evening tears flowed from his eyes, he multiplied

the prostrations he made with his face to the ground, his feet together and

rooted to the spot on which he stood. He prayed assiduously to the Mother of

God with sighs and tears, and as though the Lord was physically present he fell

at His most pure feet, while like the blind man he besought mercy and asked

that the eyes of his soul should be opened. As his prayers lasted longer every

evening, he continued in this way until midnight, never growing slack or

indolent during this period, his whole body under control, not moving his eyes

or looking up. He stood still as a statue or a bodiless spirit.

One day, as

he stood repeating more in his intellect [not the discursive reason but the

nous, the faculty that allows us to have unmediated apprehension of God--W.G.]

than with his mouth the words, 'God, have mercy upon me, a sinner' (Luke

18:13), suddenly a profuse flood of divine light appeared above him and filled

the whole room. As this happened the young man lost his bearings, forgetting

whether he was in a house or under a roof; for he saw nothing but light around

him and did not even know that he stood upon the earth. He had no fear of

falling, or awareness of the world, nor did any of those things that beset men

and bodily beings enter his mind. Instead he was wholly united to non-material

light, so much so that it seemed to him that he himself had been transformed

into light. Oblivious of all else, he was filled with tears and with

inexpressible joy and gladness. Then his intellect ascended to heaven and

beheld another light, more lucid than the first. Miraculously there appeared to

him, standing close to that light, the holy, angelic elder of whom we have

spoken and who had given him the short rule and the book.

When I

heard this story, I thought how greatly the intercession of this saint had

helped the young man, and how God had chosen to show him to what heights of

virtue the holy man had attained.

When this

vision was over and the young man, as he told me, had come back to himself, he

was struck with joy and amazement. He wept with all his heart, and sweetness

mingled with his tears. Finally he fell on his bed, and at that moment the cock

crowed, announcing the middle of the night. Shortly after the church bells rang

for matins and he got up as usual to chant the office, not having had a thought

of sleep during the whole night.

As God

knows - for He brings things about according to decisions of which He alone is

aware - all this happened without the young man having done anything more than

you have heard. But what he did he did with true faith and unhesitating expectation.

And let it not be said that he did these things by way of an experiment, for he

had never spoken or thought of acting in such a spirit. Indeed, to make

experiments and to try things out is evidence of a lack of faith. On the

contrary, after rejecting every passion charged and self-indulgent thought this

young man, as he himself assured me, paid such attention to what his conscience

said that he regarded all material things of life with indifference, and did

not even find pleasure in food and drink, or want to partake of them

frequently.

As

confused and materialistic as Southerners have become in recent decades, there

still remains a strong desire among many of them to find Christ. The true Christ is waiting for them in the

Orthodox Church.

--

Holy

Ælfred the Great, King of England, South Patron, pray for us sinners at the Souð, unworthy though we are!

Anathema

to the Union!