In

an essay by John Sanidopoulos, the following is written about the resemblances

between the Boston of Old England and the Boston of New England:

Saint

Botolph's Church began its construction in 1309 and completed in 1390. The

church tower, famously known as Boston's Stump or The Stump, was erected in

1425 and took another 90 years to complete. It is the highest tower of any

parish church in England at 272 feet built to navigate ships six miles away. It

is of this tower with its beacon and its bells that we hear in Jean Ingelow's

touching poem, "High Tide On the Coast of Lincoln shire." . . .

The people

of Lincolnshire modeled many things in new Boston based on old Boston. On March

4, 1634 the Court of Assistants in new Boston, remembering the Stump of Saint Botolph's

Church, passed the following resolution: "It is ordered that there shall

be forth with a beacon set on the Centry hill at Boston to give notice to the

Country of any danger, and that there shall be a ward of one person kept there

from the first of April to the last of September; and that upon the discovery

of any danger the beacon shall be fired, an alarm given, as also messengers

presently sent by that town where the danger is discovered to all other towns

within this jurisdiction." This also helps us to understand the

significance of the light at Boston's Old North Church in today's North End

that sparked the Revolutionary War and signaled the famous ride of Paul Revere.

Nathaniel

Hawthorne traveled to old Boston in Lincolnshire. He hints that the winding streets

of new Boston can be attributed to old St. Botolph's town: "Its crooked

streets and narrow lanes reminded me much of Hanover Street, Ann Street, and

other portions of our American Boston. It is not unreasonable to suppose that

the local habits and recollections of the first settlers may have had some

influence on the physical character of the streets and houses in the New

England metropolis; at any rate here is a similar intricacy of bewildering lanes

and a number of old peaked and projecting storied dwellings, such as I used to

see there in my boyish days. It is singular what a home feeling and sense of

kindred I derived from this hereditary connection and fancied physiognomical

resemblance between the old town and its well-grown daughter."

The

relationship between old Boston and new Boston is beautifully expressed by New England

poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem, “Boston”:

St.

Botolph’s Town! Hither across the plains

And fens of

Lincolnshire, in garb austere,

There came a

Saxon monk, and founded here

A Priory,

pillaged by marauding Danes,

So that

thereof no vestige now remains;

Only a name,

that, spoken loud and clear,

And echoed

in another hemisphere,

Survives the

sculptured walls and painted panes.

St.

Botolph’s Town! Far over leagues of land

And leagues

of sea looks forth its noble tower,

And far

around the chiming bells are heard;

So may that

sacred name forever stand

A landmark,

and a symbol of the power,

That

lies concentred in a single word.

What

is most remarkable about both Bostons, as one may be suspecting at this point,

is that they are named for a saint of the Orthodox Church, St Botolph of

Ikanhoe in Suffolk. The details of his

life are given here:

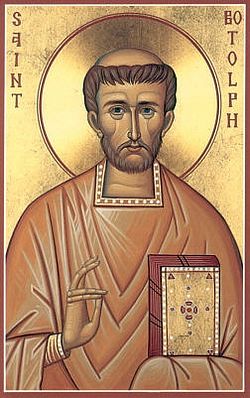

Our Holy Father

Botolph, Abbot of the Monastery of Ikanhoe (680)

'Saint Botolph was

born in Britain about the year 610 and in his youth became a monk in Gaul. The

sisters of Ethelmund, King of East Anglia, who were also sent to Gaul to learn

the monastic discipline, met Saint Botolph, and learning of his intention to

return to Britain, bade their brother the King grant him land on which to found

a monastery. Hearing the King's offer, Saint Botolph asked for land not already

in any man's possession, not wishing that his gain should come through

another's loss, and chose a certain desolate place called Ikanhoe. At his

coming, the demons inhabiting Ikanhoe rose up against him with tumult, threats,

and horrible apparitions, but the Saint drove them away with the sign of the

Cross and his prayer. Through his monastery he established in England the rule

of monastic life that he had learned in Gaul. He worked signs and wonders, had

the gift of prophecy, and "was distinguished for his sweetness of

disposition and affability." In the last years of his life he bore a

certain painful sickness with great patience, giving thanks like Job and

continuing to instruct his spiritual children in the rules of the monastic life.

He fell asleep in peace about the year 680. His relics were later found

incorrupt, and giving off a sweet fragrance. The place where he founded his

monastery came to be called "Botolphson" (from either "Botolph's

stone" or "Botolph's town") which was later contracted to

"Boston."' (Great Horologion)

--John Brady, http://www.abbamoses.com/months/june.html, entry for 17 June. For more on St Botolph: http://orthochristian.com/71898.html

Though

New England has gone far astray from the Orthodox Faith of the Holy Apostles,

which was practiced for hundreds of years in their homeland of eastern England

before the Norman Invasion of the Roman Catholics and then the Protestant

Reformation, there remains nevertheless an Orthodox root on the Yankee tree;

the name of the Queen City of New England, Boston, is proof of this, as well as

the following:

.

. . while driving through Boston along Massachusetts Avenue, I noticed that the

street running parallel to Huntington Avenue was named St. Botolph Street.

Though there is no church dedicated to Saint Botolph on this street, I did

discover later on, besides the fact there is an apartment complex named after

Saint Botolph, that on Huntington Avenue itself there is a YMCA with an

Anglican chapel inside dedicated to Saint Botolph. Besides this there are few

other mentions of Saint Botolph in the city of Boston (there is a club named

after him, and the house of the president of the Jesuit-founded Boston College

is also named after the Saint). Noteworthy is the fact that pieces of the

Gothic window tracery of Lincolnshire’s Church of St. Botolph are incorporated

into the structure of Trinity Church in Boston’s Copley Square.

--Sanidopoulos article

That

root is nearly lifeless now, crowded and smothered, slashed and beaten and

burned, by various philosophies, ideologies, and heresies that New Englanders

have embraced over the years. But it is

still there, and there is still vibrant, unquenchable life in it - the True

Life of the Holy Trinity. When they

discover this, and assimilate that Life into their own, real life will begin

for them. What has come before will seem

like bitter ashes in comparison:

Puritanism, industrialism and commerce, the Rights of Man, and so on.

And

that new life in the Orthodox Church has already begun to grow in New England,

though quietly and unnoticed for now:

. . . the Orthodox are slowly laying claim to

their Saint in the hopes of sanctifying their city in the New World, as is

traditionally done in the more Orthodox countries of the East. Besides the

awareness Holy Transfiguration Monastery is promoting through their icon of

Saint Botolph, there is also a Russian Orthodox Church Abroad parish in

Roslindale named after Holy Epiphany that depicts an icon of Saint Botolph

(painted by parishioner Zoya Shcheglov) on its south wall facing towards the

city in full stature and giving blessing to the city that bears his name. Unfortunately

there is no Orthodox church or chapel dedicated to Saint Botolph in Boston as

of yet, but there is an Antiochian Orthodox Church dedicated to Saint Botolph

in London.

--Sanidopoulos article

May

it grow into the splendid likeness of the tree that grew up in the east of

England in her Orthodox days, which was full of holy saints:

We

look forward with eagerness to the fruits the Lord will bring forth from the

New England folk when the names of Sts Botolph, Audrey, Edmund, Felix, and

others like them are honored, rather than those of Mather, Winthrop, Adams,

Emerson, or Dickinson.

The

end of Fr Andrew’s post just above on the 112 Saints of the fens in the east of

England is as fitting for overly rationalistic/scientistic New England just as

much it is for Old England, so we will use it in closing this post as well:

Conclusion: Academia

or Holiness

The Fens, the

majority of which lie in Cambridgeshire, were once notable for the port of

Cambridge, by the bridge over the River Cam. Situated at their southern limit,

this location on the river by a bridge was the very reason for Cambridge’s

existence. However, as we know, Cambridge has for centuries no longer been a

port and rather became famed as a University, as a centre of rationalistic

thinking and brainpower. In this way it opposed itself to the ascetic life of

the Saints of the Fen Thebaid to the north. What a witness it would be if there

were once more an Orthodox church in the Fens, expressing our veneration not of

rationalism, but of asceticism, not of scientists, but of ascetic fendwellers,

not of brainpower but of spiritpower. May God’s Will be done.

The

Yankees are not just a nemesis or a foil for the South; they are our cousins,

and we want the best for them just as we do for any people. We hope, then, that they will find their way

back to the Orthodox Church, the Church of their first and oldest Christian

forefathers, and to all the blessings that come from loving her, Christ’s One True

Body.

Holy

icon of St Botolph from http://orthochristian.com/71898.html .

--

Holy Ælfred the Great, King of England,

South Patron, pray for us sinners at the Souð,

unworthy though we are!

Anathema to the Union!

No comments:

Post a Comment